What's for Supper - pasta with roasted tomato sauce or how to purée garlic and the transforming powers of salt

There are dishes that I cook over and over, and have done since I first started cooking a very long time ago. They are all simple, and their addictive deliciousness comes from doing very little to good ingredients.

Out of those, some are so much a part of my routine that I cook them weekly. Roast chicken (not least for that best of leftovers, cold chicken) a soup made from seasonal vegetables and pasta with some sort of plant based accompaniment. I love the southern Italian pasta dishes in particular. The dishes from this parched tip of the country are totally different from those of the north, where rich pasture land have given birth to meat and dairy rich dishes such as the classic sauce from Bologna. In the south, the holy trinity of tomatoes, garlic and chilli are put to good use.

Since I started cooking while at Uni, doing a History of Art degree, I have cooked pasta with tomato sauce, in some shape or form. The flavours I crave when I make it have remained the same: sweet, hot and umami - almost Asian in profile, as acidity also underpins it.

In my opinion, Tomatoes must never be deprived of the company of their best friend in the kitchen; sugar.

Unless picked ripe from a sun drenched branch, tomatoes are very high in acidity and the difference a teaspoon of caster sugar, or a lug of Balsamic vinegar makes to any sauce in which tomatoes play a part is huge. My latest discovery, borrowed from a completely different cuisine, is that Pomegranate molasses also work exceptionally well with tomatoes.

When we teach in the school, guests are often surprised at how gadget free our state of the art kitchen is. Apart from our Neff hobs and ovens, our Kenwood blenders and our knives, we don't use gadgets. One of the first thing our attendees scan the table for are garlic presses. We don't have them as garlic puréed with sea salt is infinitely better in every way.

Salt, added to a raw animal protein, whether a plant or from an animal, will draw out liquid from the protein. This is why you should avoid adding salt to a nice piece of steak, chicken or fish until just before it goes in the oven or pan. If you leave salt to sit on the protein you are planning to cook, it will result in a wet surface, which means when you come to cook it it, it won't brown or caramelise, it will simply stew and result in a grey, unappetising look with inferior flavour. The caramelising you achieve by browning is essential for flavour. Contrary to popular belief, browning does not seal in juices. Only resting does that.

My rule of thumb is rest meat for at least as long as it cooked for. A rack of lamb cooked for 16-17 minutes should rest for 16-17 minutes. The exceptions to the rule are obvious; a steak, cooked rare for only a couple of minutes, benefits from resting for longer than that and a large leg of lamb or a chicken obviously does not require resting for up to an hour, but 15-20 minutes will ensure that the juices are retained in the meat so that when it is carved, they juices won't simply go to waste on your carving board.

Capitalising on the liquid-drawing powers of salt when preparing garlic stops it from burning and also results in superior flavour. All cooks will have added raw garlic to a pan of hot fat and seen in go from creamy white to little bits of burnt charcoal in seconds. Burning garlic results in little bitter tasting, crisp pieces of charcoal scattered through the dish it underpins. This is where salt comes in.

Start by placing the flat side of a large chef's knife on a garlic clove and give it a good bash with your fist to split the skin, then peel. Next, roughly chop the garlic and add about a third of its volume in sea salt. Now, place a couple of fingers on the flat side of the tip and use it as if it were the beak of a little bird, pecking into the salt and garlic. Keep pecking away - some bits of garlic will go flying - and you will immediately see how the salt teases out water from the garlic. Continue working the tip of the knife though the garlic for about a minute. When the salt has melted and the bits of garlic have started to disintegrate, stop pecking and move your fingers further down the flat blade of the knife, so that the flat of your fingers are pressing down on the knife and paddle across the board, smearing the garlic back and forth. Within seconds it will transform into a paste.

This wet garlic paste will not burn. Instead it will blend and integrate well with the other ingredients and the flavour will be more subtle, almost almond-like.

This is how:

Now for my long standing favourite version of tomato sauce.

The ingredients are simple: fresh cherry tomatoes, of which there seems to be a constant abundance, garlic, sea salt, chilli flakes, tomato purée, caster sugar and fresh basil. If you happen to have a bottle of Pomegranate molasses in your cupboards, add a splash of that too or add a little splash of Balsamic vinegar towards the end of cooking.

And of course, we want grated Parmesan. If you don't have Parmesan, any mature hard cheese will do just as fine. A strong Cheddar, or even better, one of my two all time favourite Alpine cheeses, Gruyère or Comté will taste fantastic. Dare I say it, even more delicious in this context than Parmesan.

I like chucking roughly 1/3 of the tomatoes in the oven with a bit if salt and sugar and a drizzle of olive oil and roast them at 180C ish while I cook down the remaining 2/3 in a pan with puréed garlic, a good squirt of tomato purée, caster sugar and a sprig of basil. I start with the garlic and tomato, and as soon as they start to break down, say 3 minutes of cooking, I add the rest and a good splash of water or red wine, or a mix of both. Stir and simmer for 5-10 minutes. No need to add salt - there is plenty in the garlic.

Let the tomatoes in the pan simmer down and break up, giving them a helping stir with a wooden spoon every now and then and adding a little water if the sauce is cooking down very thick. The tomato purée will thicken the sauce quite a lot.

Cooking down the tomatoes - a little film clip here

Tip the oven roasted tomatoes, with their cooking juiced, into the pan. Check the seasoning, adding more sugar if there is not sufficient underlying sweetness in the tomatoes yet.

Meanwhile you will have cooked your pasta al dente.

How to cook perfect pasta

You need a really large saucepan, and 1 small tablespoon of salt per litre. That's right - 1 tablespoon of salt per litre. Nothing else - no oil. It is the volume of water which ensures that pasta strands don't stick. Cook your chosen pasta for a couple of minutes less than suggested on the pack. The salt and shorter cooking time will ensure al dente pasta - that is to say pasta that is cooked, yet retains a little bite at the core, easing the effect of this rich dish on your gut and on your blood sugar levels. For Bucatini this means about 8-9 minutes. When cooked, lift the pasta using a pasta fork - don't drain into a colander. This removes the need for dangerous lifting and moving of large pans full of hot water and also eliminates the risk of burns to hands and lower arms. The purpose for the cook, however, is to transfer pasta straight out of the water and into the waiting sauce. If you have never tried this you'll be amazed at the difference it makes to any pasta dish, compared to topping quickly drying pasta with a sauce.

My choice of pasta is, as always, Bucatini - long hollow pasta tubes. They have more texture and bite to them than other thin pasta and the hollow centre interacts very pleasingly with the sauce when being devoured.

Bring the salted water to a rolling boil. This is what a rolling boil looks like. Don't put a lid on and keep an eye on the pan. Give the pasta a stir when it first goes in.

The pasta has been added to the sauce, not the other way around.

Buon apetito!

What's for Supper tomorrow

Some of you have asked for my recipe for cinnamon buns, the Swedish Kanelbullar.

What's for Supper - a plant based Indian supper

Here come a delicious selection of recipes from the much loved and much respected Jackie Hobbs. Jackie, like the rest of the team, trained at Leiths and had a previous life as a biology teacher. A science background is very often the launch pad for a career in food. One of our team has a previous career as a nurse, another worked for a well know plant research company. I started the business as a result of inspiration acquired while working as a finder of emerging trends in global consumer behaviour for large food brands. We all share a solid, classic training acquired at Leiths and/or Le Cordon Bleu.

When I emailed Jackie to ask what she was cooking, she replied with these mouth watering, plant based Indian supper of Basmati rice, red lentil Dahl, roasted sweet potato, coconut relish and a cucumber and mint Raita.

Dhal

The term Dhal is used on the Indian sub continent to describe dried, split pulses, ie peas, lentils and beans. These pulses constitute a cheap and excellent source of protein in areas where religion stipulates a vegetarian diet.

The word garam refers to "heating the body" in the Ayurvedic sense of the word, as these spices are believed to elevate body temperature in Ayurvedic medicine.

Pulses

300g red lentils, washed

1 litre of water

1 tsp of salt

1 tin of chopped tomatoes

1 ½ tsp turmeric

Squeeze of lemon juice, fresh chopped coriander

Tarka

2 tablespoon vegetable oil

1 tablespoon butter

1 tsp cumin seeds

1 onion chopped

5 cloves garlic

2 tsp ground coriander

1tsp garam masala

salt

1.Place lentils in a pan with the salt, tinned tomatoes and turmeric. Cover with water

bring to the boil

Remove the froth, reduce the heat and put the lid on the pan – leave to

simmer for 10 minutes. Check the lentils are cooked by squeezing them

between your fingers. Once soft remove from the heat.

2.In a frying pan, heat the oil and butter and add the cumin seeds and cook for 30 sec

onds.Add the onion and garlic to the spice, fry until lightly browned. Reduce the heat

and add the ground coriander and salt.

3.Gently let the ingredients cook for 10 minutes to make a thick masala paste.

Add a ladle full of the lentils (dhal) to the masala paste in the frying pan and stir

together then empty all the contents back into the pan with the lentils

and stir. It should have the consistency of a thick soup but if it's too thick

just add a little boiling water and remove from the heat. If you prefer it

thicker just leave it on the heat to reduce until you get the consistency you

want.

4.Check the seasoning and add a salt- it tends to be required. Stir in the garam

masala powder, a squeeze of lemon juice and fresh chopped coriander.

The sweet potatoes are simply washed, cut into cubes, tossed in oil and roasted, with cumin and fennel seeds, for 30minutes at 200C.

Coconut relish is another super simple, yet utterly delicious little dish made from desiccated coconut which is left to soak in hot water for a few minutes and mixed with mustard seeds and curry leaves, which have been fried in oil together with some red chilli and fresh ginger. This lovely combination is rounded off with a yoghurt Raita made, as always, with full fat natural yoghurt and fresh mint leaves and grated cucumber.

What's for Supper - LOVE!

I often reflect on the amazing skills we have in our group of Leiths and Cordon Bleu trained teaching chefs. Not just the rigorous, classical training, but years of cooking for ourselves, for partners and children, and now, for ageing parents. Never has it been more obvious than now, that home made food is an expression of love, of care and of nurturing and never mere sustenance.

Love underpins and defines home cooked food and also the amazing food created by people who are passionate about extending the same level of love to guests in independent cafés, bistros and restaurants up and down the country. This love is a stark contrast to the big global chains of fast food and, sadly, increasingly of smaller chains representing more "exclusive" brands, purporting to replicate what the initial flag ship restaurant once made.

You will all have visited places where the name above the door and the prices of the menus reflect a more upmarket original restaurant but where, unbeknownst to customers, every single dish will have been shipped in from a central production kitchen, even down to cartons of already whisked and seasoned eggs for scramble, and where the "chefs" behind the scenes cook nothing from scratch. Customers are not lied to outright - the beef is beef and the sour dough is a sour dough - simply helped - wrongly as it happens - to assume that the dishes carried out to the tables have been made by chefs in that kitchen, when they have in fact been mass produced in some distant industrial style kitchen, delivered and then assembled and re-heated.

Having the training from institutions such as Le Cordon Bleu is a bit like going through the Royal School of Ballet - it instils rigorous, sound, proven skills on which more experimental, modern creations can be built. It means that our team conveys the absolute best and most solid of skills which we combine with, between us, more than 200 years of cooking both at home and commercially! Best not reflect for too long on how old that makes us. There are 6 of us so you can do the maths...

We love sharing what we know, that is why we teach. The aim is never to show off or, god forbid, intimidate. The aim is simply to be as generous as we can, and fit in as much as is humanely possible of culinary skills, in the 4 hours we have at our disposal in any given class. We want to inspire and we love it when we witness that Eureka moment of "ah...I get it! THAT is why my bread was dense/my pastry collapsed/my soufflé sank/my sauce split/my pork is dry..."etc etc

Good food is love. It brings well being. It underpins our health. It has never been more important than now to reflect on how we eat, and what we eat. We have grown reluctant to make food for ourselves and for our families, and we choose instead to rely on, and to unquestioningly trust, mass produced, processed food made out of sight and for which the sustainability, quality and nutritional levels are unknown and completely out of our control.

It is the willing surrendering of control, of input, which I find so surprising. Freedom of choice, making decisions for every aspect of our daily lives is something we take for granted and cherish in a welfare democracy. Yet, for that most vital ingredient, the daily food we give our children and ourselves, we surrender all control and ask no questions.

Instead, we are easily and readily seduced by every new fad and trend, hungry and hopeful for some kind of miracle food flown in from far flung countries, which will deliver eternal life, when the simple fact is that, alongside a bit of regular exercise, cooking normal, every day food from scratch, using sustainable, local ingredients is your best bet for a long and healthy life.

When we cook, we see the raw and unadulterated ingredients that you use. It simply isn't possible to add levels of salt or sugar which could be bad for our health because the ensuing dish would quite simply be inedible. Just revolting. However, the many artificial sweeteners in ready made sauces, the salt added even to sweet foods such as cereal, you can't taste. All we taste are the savoury, fatty and sweet flavours which the big food manufacturers know will give the brain a high and keep all of us coming back for more.

To stay healthy, we must cook our own food. To stay engaged, we need to reconnect with food.

To sustain ourselves and our children, we need to take back control of what we put through our bodies.

I absolutely do not buy the argument that cooking from scratch is a privilege only the well to do can afford. A little bit of knowledge is all it takes to cook and to do so on a modest budget. I regularly cook food with a per portion price well below £1, often below 50p. Obtaining food at such low cost is simply not possible if the food is processed ready meals, or deliveries from chains. Lend me a tenner and I will promise you I can buy ingredients from which I can create delicious meals for a full week.

This is why cooking, taught in a relevant and enjoyable way, needs to be put back on the curriculum in schools. Government initiatives have so far failed to curtail the all-powerful global food industry. If we get our children involved in cooking with us at home, helping working parents by preparing for suppers, and shift the focus to teaching the next generation how to cook we will help them to love and expect the taste of normal home made food. That in turn will lead to a change in shopping habits which will benefit producers of ingredients, not meals, that is to say farmers, in particular small scale ones, sustainable fishing, and outlets such as green grocers and markets, rather than large scale manufacturers of processed food and pan global supermarkets whose unholy alliance have been undermining our health over then past decades. It is not just our personal health which is undermined, it is the environment. Mass produced food, quite simply, is the opposite of love and life.

So what are we waiting for? Let's get cooking and let's get the kids and teens cooking! Dig a little vegetable garden, plant some seeds for the windowsill, accompany your kids to the entrance of your nearest food shop, with a tenner worth of credit on a card, and ask them to come back out with ingredients for at least 2 family meals.

What's for Supper - Easter Sunday with confit salmon & oven dried tomatoes with celeriac mash

After so many warm and sunny weeks in Cambridge, I am glad to be using up the last of my winter root vegetables, which were stored in a shady corner of my balcony. With this mash, the last Celeriac of the season goes and I am now mentally and culinarily ready to move on to new potatoes and asparagus!

In French, confit, means a preserve, a jam, and it is the kitchen term for cooking something slowly with an aim to preserve it. The food can be slow cooked in oil, or a sugar and water, at low temperatures over a longer period of time than cooking at normal temperatures would require. The most well known savoury dish is confit duck, where the slow cooked duck legs are left to cool down, and kept completely buried in the cooking fats, thus hermetically sealed in. This method allows for fresh duck to be kept for months on end. When using confit'ing to cook fish or vegetables at low temperature, in a fat, the aim is not so much to preserve, more to gain the benefits which are unrivalled succulence and none of the usual dimming of colour associated with other cooking methods. The green of vegetables is just as vibrant after being confit'ed as is the bright red of wild salmon.

The results are similar to those acquired by sous vide cooking (sous vide meaning "under vacuum"), where food is vacuum packed into plastic bags before being immersed in a water bath and kept at a constant low temperature for many hours, often over night, so it's ready to quickly brown and serve for service. It cuts down on waste, as there is no shrinkage during cooking, it makes the work of chefs infinitely easier as there is no need to check the food while cooking to gauge if the interior temperature and consistency is exactly as required when there is only the exterior to go by; and it also guarantees the same result over and over. So a method introduced to make life in big kitchens easier, became all the rage as it results in tender, succulent and vibrant looking food, cooked in its own juices.

Slow cooking at low temperature, in oil, results in meltingly delicious and soft protein, plant and animal based. I tend to give my confit salmon a Swedish touch by gently rubbing in sea salt and sugar and leaving it like that for about 30 minutes before I cook it. Today I added some rosemary as well, before immersing it in olive oil and cooking it at 70C - one of the very lowest settings for my oven. The time depends on the size of the pieces of salmon, but for small pieces like mine, about half an hour sufficed. The fish should be cooked - just - but won't be firm as it is when oven roasted or pan fried, but tender and soft.

While so many shelves were empty in the shops after those frantic days before lock down, one shelf remained miraculously resplendent; the tomato shelf. Either we have a serious over supply of tomatoes or tomatoes were rejected in the rush to buy long life ingredients. I decided to use another slow cooking method for my ample supply of cherry tomatoes - oven drying until demi-sec, not totally dried. I added some sliced lemon and some more of my fresh rosemary, sprinkled on sea salt and tiny bit of sugar, poured a little oil over and left them in an oven for 90 minutes, at a temperature of 120C.

With both the salmon and the tomatoes taking care of themselves in the oven, I turned my attention to making celeriac mash. Cut away the skin, cut into cubes, simmer in salted water until soft, mash. Beat in butter and a little full fat milk. I always add a little cream, if I have it, to any mash I make. I often throw in one large, cubed, King Edward potato with a celeriac or parsnip mash as it gives a smoother texture when mashed. For one celeriac I used almost 100g butter and about 100ml milk/cream. Rich, yes, but serving 8 (with my portion control, anyway) that is not bad. And it is a treat. If you are keen to restrict fat, the you could roast the celeriac, whole, wrapped in foil, for a couple if hours, or slice it and cook with with already softened sliced onion, in a stock, to make a delicious Boulangère or bake it with a few knobs of butter, some herbs and a few good splashes of that favourite stove side tipple of mine, Marsala wine!

What's for supper tomorrow

Delicious plant based, Indian inspired favourites from another outstanding chef on our team, Jackie Hobbs. A bank holiday feast of Red lentil Dahl, roasted sweet potato with fennel and cumin, Coconut relish and yoghourt raita with mint and cucumber. Join us at the table!

What's for Supper - Easy Easter lunch

We have so much skill in our group of Leiths and Cordon Bleu trained teaching chefs.

We also still love cooking at home and recipe sharing and talking about what we have made remains a daily joy.

Of course there are days and nights when we are too tired to feel inspired and that's when leftovers come into their own. The more you cook from scratch, the more delicious leftovers you have and the less money you spend on food.

Cold chicken is a shared all time favourite and we all like roasting more than we need just to make sure there is cold chicken. Enjoying it with a dark rye, mayonnaise, sweet pickled gherkins, jalapeño peppers, pickles or mustard is just so good.

Of course you can also pick the scraps off the carcass and use it in fragrant Thai style noodle soups, curries, salads or pies. The options are endless.

Today's recipes comes from our chef Caroline Sandford, whose wonderful teaching has inspired so many over the years, not least those who have taken our 8-week course where we teach all the classic essentials for those seeking a slightly more professional grounding in the art of cooking. A mother of 6, now all teens and young adults, we are in awe of Caroline's serene and unflappable approach to any challenge. These recipes reflect the style of cooking that has sustained her very lucky family over the years. Good, simple ingredients, delicious and healthy dishes and often using store cupboard ingredients.

Curried Parsnip Soup

Approx. 50g butter

1 onion chopped

1 clove garlic crushed

1 teaspoon mild or medium curry powder

4 parsnips cubed

Approx. 30g flour

1 tbs flour

1 litre chicken stock well seasoned

Milk and / or single cream

Salt and pepper

Lemon juice

Chives chopped

Soften onion in butter, add garlic. Add curry powder, cook few mins. Add parsnips sprinkle in flour and cook a little more. Add the stock and leave to simmer gently until parsnips are cooked. Blend in processor or using a stick blender. Add milk/ cream to achieve right consistency. Season to taste, with salt , pepper and lemon juice. Garnish with créme fraîche and snipped chives.

Homemade Baked Beans

1 onion finely chopped1 Stick of celery finely chopped1 clove garlic, puréed with sea saltA small squirt of tomato purée1/2 teaspoon smoked paprikaApprox. 150 ml passataSoy sauce2 tsp brown sugar1 tin cannellini beans, drainedSalt and pepperFlat leaf parsley

- Soften onion and celery in a little sunflower oil. Add garlic followed by tomato purée and paprika, cook for a minute, then add passata, soy, brown sugar. Reduce a little, check seasoning then add beans to heat through. Garnish with parsley. Quick and delicious.

Roast chicken

1 whole chicken

1 lemon

A few wedges of onion (optional)

Hard herbs such as thyme, tarragon or rosemary

Sea salt and ground black pepper

Olive oil or butter for the chicken skin

- Set the oven at 190C.

- Prick the lemon a few times with the tip of a knife

- In the roasting tin, pour a tablespoon of sunflower oil

- Add to it a very generous few pinches of salt and pepper

- Roll the lemon in it, then push into the chicken carcass

- Push in the herbs

- Place the chicken in the tin

- Drizzle a little olive oil or smear some soft butter over the chicken and season with salt and

- pepper

- No matter how small the chicken, roast for an hour.

- For a medium chicken (1.2-1.5kg) roast for 1 hour 15 min

- For a large chicken (1.5-2.5kg) roast for 1 hour and a half

- To check that the chicken is cooked, remove the tin from the oven

- Insert into the thickest part of a thigh, the tip of a knife and gently press on the thigh

- The juices that run out should be clear. If pink or red, put it back in the oven and check again after 10 minutes.

Remove the roasting tray from the oven and let the kitchen sit to cool down for 10-12 minutes. This will keep it juicy. It will still be very warm, just not piping hot when you carve it. The chicken meat should be succulent, tender and moist. Far too often chicken is served way past its "done" point which means the meat is dry and dull. Cold chicken, and any leftover roast potatoes and veg is one of life's absolute joys. With dark rye and mayonnaise it is addictively good. You could roast two smaller chickens instead of one larger, to make sure there is plenty for leftovers.

What's for supper tomorrow

An easy Easter Sunday lunch of confit salmon, oven fried cherry tomatoes, in my case served with a celeriac mash. I need to use up the final celeriac of the past 5 months. Such a delicious and versatile root vegetable which has been a weekly, sometimes daily ingredient in my winter cooking both at home and in the café. I now turn my eyes and thoughts to that most special of seasonal crops - asparagus...

What's for Supper Easter special: Hot Cross Buns

Hot Cross Buns

This recipe comes from our chef and artisan baker Clare Bermingham. Clare, like the rest of us here at the Cookery School, trained at Leiths but then also went on to train as a baker with Le Cordon Bleu.

If you have attended one of the bread classes run by Clare, either alone or with your child as part of our many popular Parent & Child classes, you will know what an amazing baker she is. Watching Clare knead, shape and touch dough tends to have a transfixing, and ultimately, life transforming effect on those who attend!

As we are aware that freezer space may be limited at the moment, Clare has offered a relatively small quantity, making 6 buns. Obviously if you would like to make a dozen, simply double the recipe!

For the dough

200g strong bread flour

50g wholemeal flour

5g salt

3.5g (1/2 sachet) quick action yeast, or 10g fresh yeast, if you have it

110g full fat milk, heated to just about lukewarm

25g mixed peel (or cranberries)

100g raisins or sultanas

1 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1/2 teaspoon ground cloves

1/4 teaspoon ground allspice

1/2 teaspoon ground or freshly grated nutmeg

1 medium egg

25g soft butter

20g runny honey, or golden syrup

For the crosses

Mix equal quantities flour and water, to form a fairly thick paste, then add a little caster sugar

For the glaze

Warmed and sieved apricot jam

- In a bowl, combine the flours, spices and salt.

- Dissolve the quick action yeast in the luke-warm milk, add the egg, butter and honey

- Add the dry ingredients to the wet.

- Mix to form a dough, then tip out onto your work surface and knead for about 10 minutes using the base of your palm, pushing dough away from you to stretch it, then fold it back on itself. Repeat. The stretching creates gluten, the folding helps to trap air for the yeast to work in.

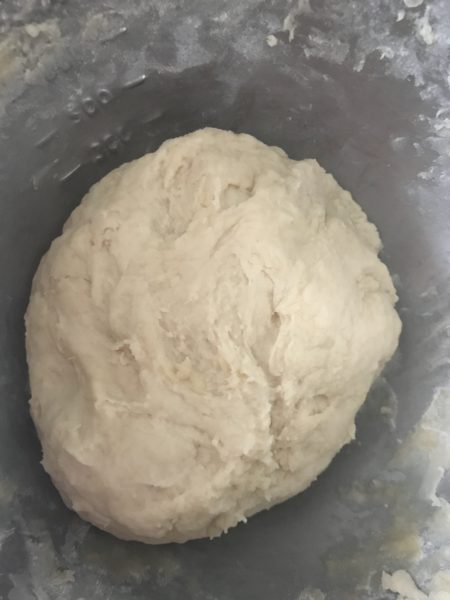

You will see how the dough changes from "ropey" and ragged, as above, to looking glossy and smooth. To find out if you have kneaded enough to create the gluten needed for good bread, do a "gluten window" test as shown in the little clip here. You should be able to stretch a thin membrane without the dough breaking. If it breaks up, knead for another 30-60 seconds - it can be that quick. Gluten is made by mixing flour and a liquid and then stretching and manipulating it and creating molecular gluten strands to give the buns their lovely texture.

You will see how the dough changes from "ropey" and ragged, as above, to looking glossy and smooth. To find out if you have kneaded enough to create the gluten needed for good bread, do a "gluten window" test as shown in the little clip here. You should be able to stretch a thin membrane without the dough breaking. If it breaks up, knead for another 30-60 seconds - it can be that quick. Gluten is made by mixing flour and a liquid and then stretching and manipulating it and creating molecular gluten strands to give the buns their lovely texture. - Leave to rise for an hour, covered by a clean tea towel and away from draughts.

- When the dough has doubled in size, add the raisins and mixed peel and re-knead.

- Divide into 6 equal parts, and shape into little buns. See Bread roll blog for shaping technique.

- Place on a baking tray, if you like, so close that they are lightly touching and will need to be gently prized apart once baked.

- Prove for at least one hour.

- Meanwhile, set the oven to 190C. Mix the flour, water and sugar. Spoon into a piping or plastic bag, and pipe out over all the buns, so they are all "crossed".

- Bake for 20 minutes, or until golden brown.

- While still warm, brush liberally with the apricot glaze and leave to cool on the rack.

What's for Supper Cake special: Cambridge Cookery gluten free Sea salt Brownies

Our Brownies and Swedish cinnamon buns, baked after my Grandmother Greta's recipes, are our signature bakes. Each day, a batch of each goes on the counter first thing at 9am. By mid morning we put out a second round and late lunch time we usually put out a third.

This recipe was originally tweaked into perfection by my youngest daughter when she was 14 or 15. An engineer, who by her own admission is happiest if she is not required to perform any kind of domestic activity, she surprised herself, as much those of us who know her, by producing one of the best cake recipes ever, during one rare creative afternoon in the kitchen.

I have yet to meet anyone who does not agree that these Brownies are the sine qua non of any cake counter worth its name. And the method is super easy and super quick to make!

In the café, we make these with gluten free flour but you can, of course, use normal plain flour.

As for the eggs, the hot tip of the day is that eggs can be frozen. Simply crack and pour into freezer bags. I tend do freeze three at a time, as most of my cake recipes are based on 3 eggs.

Cambridge Cookery Brownies

200g unsalted butter

200g dark chocolate

3 large, organic eggs

1 teaspoon vanilla paste

250g caster sugar

110g gluten free or normal plain flour

1/2 teaspoon to a full teaspoon sea salt (not table salt). If you don't have sea salt I would suggest a teaspoon of dark soy sauce rather than using iodine-rich table salt. If you have never tried adding a splash of dark soy sauce to toffee, caramel or white chocolate based sauce, do! It is sensational.

1. Pre-heat the oven to 180°C

2. Line a medium baking tray (slightly smaller than an A4 sheet) with baking paper.

3. Melt the butter and chocolate. You can do this in a microwave or on the hob. You don't need a Bain Marie (see blog on Béarnaise) if you melt chocolate with other ingredients such as butter or cream, as long as you do it over low heat. Remove to cool down a little.

4. Beat the eggs with the sugar and vanilla.

CLICK HERE TO SEE Texture of whisked eggs and adding chocolate

CLICK HERE TO SEE How to fold to combine

5. Once the chocolate butter mixture has cooled a fraction, pour into the eggs and sugar.

6. Sift in the flour and salt. Fold together the ingredients. Folding means using a large spoon, preferably metal, and twisting it in your hand, so it gently lifts and drops back down sections of cake mixture. It's more gentle than stirring. The less you agitate the mixture the lighter it will be.

7. Pour into the tray and bake for 16-17 minutes.

This is what my knife looks like when I run it through the baked Brownie tray.

The exact time will depend the size and depth of your baking tin and on your oven. After 15 minutes you should the see the almost lacquered top layer typical of a good Brownie. Open the oven, very gently press two fingers down on the centre of the Brownie mixture. It should feel very soft. Not so soft that you suspect that the interior is still completely liquid, but definitely nowhere near as firm as baked sponge. Be brave and err on the side of under baked, as the Brownies set as they cool down. There are thousands of recipes in circulation which result in dry Brownies and as many café counters up and down the country offering dry Brownies. So disappointing.

The exact time will depend the size and depth of your baking tin and on your oven. After 15 minutes you should the see the almost lacquered top layer typical of a good Brownie. Open the oven, very gently press two fingers down on the centre of the Brownie mixture. It should feel very soft. Not so soft that you suspect that the interior is still completely liquid, but definitely nowhere near as firm as baked sponge. Be brave and err on the side of under baked, as the Brownies set as they cool down. There are thousands of recipes in circulation which result in dry Brownies and as many café counters up and down the country offering dry Brownies. So disappointing.

CLICK HERE TO SEE CORRECT TEXTURE of Brownies

These are gooey, intensely chocolatey and have a lovely hint of saltiness to offset the high amount of sugar. I like using 70% cocoa solid dark chocolate. Anything higher is a little too bitter for me, but you may disagree and prefer a higher cocoa content.

CLICK HERE TO START SALIVATING...and listen to the sound the spoon makes as it cuts into the Brownie.

The Brownies freeze well, in the unlikely event that the whole batch does not get devoured on the day of baking. It is easiest to freeze what is left in the baking tray.

To serve, you could dust with icing sugar, add a sprig of fresh mint, then add a few berries.

Or serve as a dessert, with a dollop of sour cream or crème fraiche, as well as some fruit.

Tomorrow's recipe: Hot Cross Buns from the hand of one of our team of amazing chefs and teachers, Clare. Clare, like the rest of us, is Leiths trained. However, she stands out even among our group of exceptional bakers, through her baking skills learned at Le Cordon Bleu.

What's for Supper - Steak Béarnaise or how to beat an emulsion sauce

Larousse defines a sauce as a "liquid seasoning for food" which I think is spot on.

Emulsion sauces are in the hall of fame of classic French cooking. They are wonderfully delicious but occasionally a challenge to the home cook. Emulsion sauces, wether cold, like Vinaigrette or Mayonnaise, or warm, like Béarnaise and Hollandaise, are made by forming a suspension of tiny droplets of fat, say butter or oil, in a liquid, usually a sharp, acidic one. Depending on the ingredients and the technique, emulsion sauces are either unstable - think vinaigrette which will separate as soon as you stop shaking or whisking it - or stable - think mayonnaise. Classic French cooking have an index for sauces based on Mother sauces, from which all other sauces are derived. In the case of emulsion sauces, Hollandaise is the Mother. It is generally considered a perfect match for poached salmon or asparagus.

Its delightful daughter, Béarnaise, is my absolute favourite sauce. Hollandaise is flavoured only with a little lemon juice whereas Béarnaise is defined by tarragon, which I love. Its aniseedy flavour is one of those matches made in food heaven for chicken, beef and rich eggy things. As the amount of butter is very high - around 160g for a recipe for 4-6, so say 40g per person this is not something I should, nor would, eat daily or even weekly. But 3-4 times a year I crave rare steak, home made Béarnaise and a really good green salad or lightly cooked green beans. No carbs required. I am a protein lover.

The magic ingredient in a stable emulsion is egg yolk. Egg yolk, along with Dry English mustard powder, incidentally, are the only two natural emulsifiers of the ingredient world. Hence why emulsions with no egg, say Vinaigrette, are unstable.

There is only one example of a stable emulsion sauce which has no egg in it and that is the scariest sauce of all; Beurre Blanc. Made like a Hollandaise, minus the egg, it relies solely on temperature control and agitation of the fat molecules for success. Beurre Blanc and Puff Pastry were the two things which regularly caused mental meltdowns when I trained. Being asked to make one of these caused a reaction best illustrated by Munch's The Scream!

So, compared to that, making Béarnaise is a doddle, even when made the classic way, rather than the modern way, which places the reduction in a blender and adds melted butter while running at high speed. That's for cowards.

The classic way can be achieved with your left hand while your right hand flips a steak, and the whole glorious meal can be on a warm plate within the space of 5 minutes! The less you allow yourself to be intimidated by this sauce, the higher the success rate, in my experience. Not letting your potentially oik'ish sauce getting the better of you, and understanding the importance of temperature is the way to go. Here's how:

To make the acidic reduction

2 tablespoons white wine vinegar + 1 tablespoon of water

Some blade mace (the bark of the nutmeg tree so you can use a tiny bit of nutmeg, it's just not cosmetically desired for the sauce to have little brown specks in it) a piece of raw shallot or normal onion (I often omit this) and a sprig of tarragon and if you have whole black pepper, a few pepper berries.

Place this in a small saucepan and turn up to medium heat. Watch it like a hawk. Don't turn your back on it for a second. The liquid will reduce rapidly and disappear entirely within the blink of an eye lid. When reduced to about 1 tablespoon, take off the heat and sieve into a clean glass or metal bowl.

Creating a Bain Marie to make the sauce

A Bain Marie is a method of melting or cooking over indirect heat, to reduce the risk of something seizing or splitting.

The whole purpose of it is that the bowl of ingredients should sit above not in the simmering water beneath it. If it sits in the simmering water it is no longer indirect heat.

So pour some water into the base of a smallish saucepan.

Find a bowl which fits in the pan without sitting so deep that it touches the water in the saucepan.

To make the sauce

Before I start, I cut 160g butter into cubes and place them in the freezer for a few minutes. Constantly keeping your sauce in its place, adding ice old butter means you will deny it its attempts at being unruly and going for a split. So is controlling the heat of the hob on which you place your pan. Be prepared to quickly pull the pan off the hot plate and onto a cooler part of the hob. If you want belts and braces, keep by your side a large bowl of iced water and dunk the bowl of sauce in to it as soon as you the slightest tendency of it splitting. What are those tendencies? They are a rapid increase in oiliness followed even more rapidly by the sauce metamorphosing, like some sort of sinister Sci-fi creature, from a thickening liquid into a jelly-fish like blob, a shape shifter which means your sauce is about to get the upper hand and triumph over you, the boss. You might want to boost your morale by shouting "Who's the boss" at the sauce at regular intervals.

If you look at the image of my sauce which I used for this feature, you will in fact see the very first signs of it splitting - there is a sheen on it, which looks distinctly oily. As I took the photo, I realised what was happening, and whacked in another piece of cold butter and whisked like mad, off the heat, and that halted the decline. Ha! This sneaky attempt at mutiny from my sauce, at a moment when my focus was on taking the photo, was successfully crushed.

This little video shows how to add the butter

Or just pay attention to the temperate under the pan and watch the sauce. And keep adding that ice cold butter. At some point, add a generous pinch of sea salt.

So you start by placing the bowl of reduction, egg yolk and one or two of your pieces of cold butter over the heat. Start whisking. Agitating the molecules is your third secret weapon against mutiny from your sauce. So don't hold back. Whisk like your life depends on it. As soon as one lot of butter has melted, add two to three more cubes. Carry on like this, while keeping your eye on the sauce, and being ready to move the pan momentarily off the heat should it look dodgy. While you do this, and it will only take 5-6 minutes, caramelise the steak, over high heat in sunflower oil, for about a minute per side. This is assuming the thickness of a sirloin steak, ie about 1.5cm. Turn the heat off, add a knob of butter to the still searingly hot pan and baste the meat with it as it melts. Lift the steak out of the pan to stop any further cooking, or just push the pan off the heat, in which case the steak will continue to cook through.

Add a couple of tablespoons of chopped fresh tarragon to the sauce.

Sauce done, I tend to add just a little of the meat juices to it, just to show it how confident I am that I have won the battle - and to add lovely flavour. Slice the steak thickly, pour some sauce over. Serve with a green salad and a lovely unstable emulsion vinaigrette of 1 part red wine vinegar to 3 parts olive oil, a large pinch of sugar, a small pinch of sea salt and an even smaller pinch of freshly ground white or black pepper. Voilà!

I would be in seventh heaven if I had a Côte du Rhône such as Vacqueryas or Rasteau in my glass, or an Italian Barbera d'Alba.

Tomorrow's recipe: our legendary gluten free sea salt Chocolate Brownies

What's for Supper - Borscht

It has turned into quite a warm afternoon here in Cambridge and this Eastern European soup is more of a cold weather dish, really. The first time I tried Borscht was in a Russian restaurant in Helsinki, back in the late 1980's, on a bitterly cold evening in February. The snow covered scenery was more Russia than Scandinavia, and the food memory stands out as one of my top ten. Like most first comers to this beetroot and potato based soup, I expected it to be perhaps a tad bland, tasting mainly, I imagined, earthy. I was completely blown away by the rich, savoury, umami-redolent, deeply satisfying flavour. The contrast between the thick, rich, savoury and piping hot soup and a dollop of cool, soured Smetana and some chopped sweet pickled gherkins was sensational. I tend to use Crème Fraiche or sour cream, but you can of course exclude that bit entirely if you are Vegan. If you are a carnivore, then using beef stock for the soup helps to underpin the savoury richness, but given that all the ingredients are plant based, a good vegetable stock would be the most obvious choice.

The red pepper in my bowl is not a traditional ingredients in Borscht, but it's the right colour, and its sweetness does the soup no harm. My tomatoes are on their last leg, so perfect for soup.

Peel, chop and/or slice the following

1 onion

2 large potatoes

A couple of celery stalks

3 garlic cloves,

4 beets

1/2 small red cabbage

A couple of tomatoes - mine shown here are about to reach the end of their shelf life so perfect for soup making.

A generous splash of one of my previously mentioned stove side favourites, Marsala wine

Good beef or vegetable stock

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

To serve: Full fat Crème Fraiche, chopped sweet pickled gherkins

Heat a good lug of sunflower oil and a large knob of butter in a large saucepan.

Add all the prepared vegetables, a couple of good pinches of sea salt and a little black pepper. Sweat over a medium heat, while stirring occasionally. If you are a carnivore, using goose or duck fat instead of the oil and butter will add lovely depth.

The vegetables should be glossy from the cooking fat and should just have started to take on a little bit of colour: 5-10 minutes or so of cooking.

Add the Marsala and the stock.

Cover and leave to simmer for 25-30 minutes.

Some recipes for Borscht leave the soup as it is with the bits of vegetables but I much prefer blending it. Taste it, adjust the seasoning. I would expect to add a bit more salt and I might be tempted to add a little Balsamic vinegar or Pomegranate molasses - both utterly in-authentic but both do something very nice by introducing both acidity and sweetness at the same time.

To serve, pour very hot soup into bowls, add a good dollop of Crème Friache, and a little spoonful of chopped sweet pickled gherkins. I happened to have a stalk of rosemary in my fridge, but dill would be more in keeping with the origins of the soup.

Join me again tomorrow

As usual, no sooner have I finished one meal than I begin to think of the next. I have a very nice organic rump steak in my freezer. I could go classic French and make a Béarnaise sauce and serve the steak very rare, with a baked potato. Not your average Tuesday supper and the weather is meant to be warm, so maybe I will make steak Burritos instead. I have avocado that could do with using up so that's probably what will be on the menu tomorrow...

What's for Supper Breakfast special - 5 second scramble

In preparation for my Monday morning zoom yoga class with local teacher and café regular Helen Pomeroy, I felt some protein was in order. What better than a 5 second scramble. A healthy, lean protein breakfast, brunch or lunch which takes a total of three minutes to make if you include toasting bread, getting your utensils out, cooking and plating up! Not many dishes deliver that.

We often get asked by our guests in the café how we make our popular scramble. Fast and furious are the key words. We use eggs, a teaspoon of sunflower oil and full heat under the pan. No cream, no water and most definitely no milk.

Break up the eggs using a fork. Don't whisk, just mix to create an elastic texture.

While you do this, whack the heat up under you frying pan in which you have poured about half a teaspoon of sunflower oil. Tip in the eggs, spatula or fork at the ready - as shown in the little video clip here. Some of may shudder at the sound of my stainless steel fork in my non stick pan. There is something about plastic, silicon and rubber utensils that I find unappetising and quite annoying, so I prefer a fork, applied with a light touch. So far, my trusted pans remain unscathed.

SCRAMBLE clip

Tip the scramble onto a piece of toasted sour dough. I love adding Sriracha sauce - creamy egg and hot chilli is a match made in heaven. I am also unapologetic about my love of parsley.

What's for supper this evening

My recipe for supper this evening will be my take on Borscht - a savoury, umami-redolent, muscular Beast from the East soup. All you will need is potato, beets (raw) onion, garlic, stock...