What’s for Supper – Steak Béarnaise or how to beat an emulsion sauce

Larousse defines a sauce as a “liquid seasoning for food” which I think is spot on.

Emulsion sauces are in the hall of fame of classic French cooking. They are wonderfully delicious but occasionally a challenge to the home cook. Emulsion sauces, wether cold, like Vinaigrette or Mayonnaise, or warm, like Béarnaise and Hollandaise, are made by forming a suspension of tiny droplets of fat, say butter or oil, in a liquid, usually a sharp, acidic one. Depending on the ingredients and the technique, emulsion sauces are either unstable – think vinaigrette which will separate as soon as you stop shaking or whisking it – or stable – think mayonnaise. Classic French cooking have an index for sauces based on Mother sauces, from which all other sauces are derived. In the case of emulsion sauces, Hollandaise is the Mother. It is generally considered a perfect match for poached salmon or asparagus.

Its delightful daughter, Béarnaise, is my absolute favourite sauce. Hollandaise is flavoured only with a little lemon juice whereas Béarnaise is defined by tarragon, which I love. Its aniseedy flavour is one of those matches made in food heaven for chicken, beef and rich eggy things. As the amount of butter is very high – around 160g for a recipe for 4-6, so say 40g per person this is not something I should, nor would, eat daily or even weekly. But 3-4 times a year I crave rare steak, home made Béarnaise and a really good green salad or lightly cooked green beans. No carbs required. I am a protein lover.

The magic ingredient in a stable emulsion is egg yolk. Egg yolk, along with Dry English mustard powder, incidentally, are the only two natural emulsifiers of the ingredient world. Hence why emulsions with no egg, say Vinaigrette, are unstable.

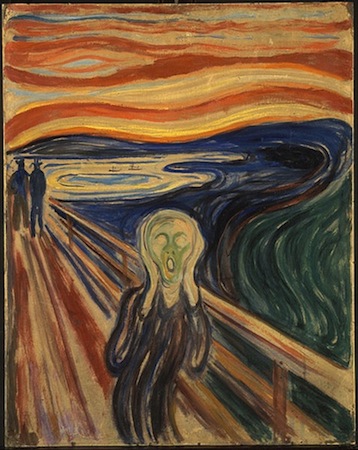

There is only one example of a stable emulsion sauce which has no egg in it and that is the scariest sauce of all; Beurre Blanc. Made like a Hollandaise, minus the egg, it relies solely on temperature control and agitation of the fat molecules for success. Beurre Blanc and Puff Pastry were the two things which regularly caused mental meltdowns when I trained. Being asked to make one of these caused a reaction best illustrated by Munch’s The Scream!

So, compared to that, making Béarnaise is a doddle, even when made the classic way, rather than the modern way, which places the reduction in a blender and adds melted butter while running at high speed. That’s for cowards.

The classic way can be achieved with your left hand while your right hand flips a steak, and the whole glorious meal can be on a warm plate within the space of 5 minutes! The less you allow yourself to be intimidated by this sauce, the higher the success rate, in my experience. Not letting your potentially oik’ish sauce getting the better of you, and understanding the importance of temperature is the way to go. Here’s how:

To make the acidic reduction

2 tablespoons white wine vinegar + 1 tablespoon of water

Some blade mace (the bark of the nutmeg tree so you can use a tiny bit of nutmeg, it’s just not cosmetically desired for the sauce to have little brown specks in it) a piece of raw shallot or normal onion (I often omit this) and a sprig of tarragon and if you have whole black pepper, a few pepper berries.

Place this in a small saucepan and turn up to medium heat. Watch it like a hawk. Don’t turn your back on it for a second. The liquid will reduce rapidly and disappear entirely within the blink of an eye lid. When reduced to about 1 tablespoon, take off the heat and sieve into a clean glass or metal bowl.

Creating a Bain Marie to make the sauce

A Bain Marie is a method of melting or cooking over indirect heat, to reduce the risk of something seizing or splitting.

The whole purpose of it is that the bowl of ingredients should sit above not in the simmering water beneath it. If it sits in the simmering water it is no longer indirect heat.

So pour some water into the base of a smallish saucepan.

Find a bowl which fits in the pan without sitting so deep that it touches the water in the saucepan.

To make the sauce

Before I start, I cut 160g butter into cubes and place them in the freezer for a few minutes. Constantly keeping your sauce in its place, adding ice old butter means you will deny it its attempts at being unruly and going for a split. So is controlling the heat of the hob on which you place your pan. Be prepared to quickly pull the pan off the hot plate and onto a cooler part of the hob. If you want belts and braces, keep by your side a large bowl of iced water and dunk the bowl of sauce in to it as soon as you the slightest tendency of it splitting. What are those tendencies? They are a rapid increase in oiliness followed even more rapidly by the sauce metamorphosing, like some sort of sinister Sci-fi creature, from a thickening liquid into a jelly-fish like blob, a shape shifter which means your sauce is about to get the upper hand and triumph over you, the boss. You might want to boost your morale by shouting “Who’s the boss” at the sauce at regular intervals.

If you look at the image of my sauce which I used for this feature, you will in fact see the very first signs of it splitting – there is a sheen on it, which looks distinctly oily. As I took the photo, I realised what was happening, and whacked in another piece of cold butter and whisked like mad, off the heat, and that halted the decline. Ha! This sneaky attempt at mutiny from my sauce, at a moment when my focus was on taking the photo, was successfully crushed.

This little video shows how to add the butter

Or just pay attention to the temperate under the pan and watch the sauce. And keep adding that ice cold butter. At some point, add a generous pinch of sea salt.

So you start by placing the bowl of reduction, egg yolk and one or two of your pieces of cold butter over the heat. Start whisking. Agitating the molecules is your third secret weapon against mutiny from your sauce. So don’t hold back. Whisk like your life depends on it. As soon as one lot of butter has melted, add two to three more cubes. Carry on like this, while keeping your eye on the sauce, and being ready to move the pan momentarily off the heat should it look dodgy. While you do this, and it will only take 5-6 minutes, caramelise the steak, over high heat in sunflower oil, for about a minute per side. This is assuming the thickness of a sirloin steak, ie about 1.5cm. Turn the heat off, add a knob of butter to the still searingly hot pan and baste the meat with it as it melts. Lift the steak out of the pan to stop any further cooking, or just push the pan off the heat, in which case the steak will continue to cook through.

Add a couple of tablespoons of chopped fresh tarragon to the sauce.

Sauce done, I tend to add just a little of the meat juices to it, just to show it how confident I am that I have won the battle – and to add lovely flavour. Slice the steak thickly, pour some sauce over. Serve with a green salad and a lovely unstable emulsion vinaigrette of 1 part red wine vinegar to 3 parts olive oil, a large pinch of sugar, a small pinch of sea salt and an even smaller pinch of freshly ground white or black pepper. Voilà!

I would be in seventh heaven if I had a Côte du Rhône such as Vacqueryas or Rasteau in my glass, or an Italian Barbera d’Alba.

Tomorrow’s recipe: our legendary gluten free sea salt Chocolate Brownies

What’s for Supper – Borscht

April 6, 2020

What’s for Supper – Nettle soup with poached egg

April 1, 2020